by Muhammad Alzaki Tristi

In Makassar, small-scale fishers from Maluku, Lombok, and Ternate speak up about quota-based fisheries policy. The government promises that they will not let their boats get brushed aside by data and quota-based policy.

Makassar, July 2025—From the red-cushioned seats of Hasanuddin University’s auditorium, voices of small-scale fishers from Maluku, Lombok, and Ternate mingled with ministry officials and academics’. For three days, this was the stage for a conversation that could shape the future of Indonesia’s seas: the government’s push for Indonesia’s Measured Fishing Policy—a quota- and data-based system meant to curb overfishing.

Outside, Makassar’s sky shifting restlessly, mirroring the intense mood exchanges indoors with rapid-fire questions, punctuated by bursts of small laughter. This was the Annual Meeting of the Fisheries Management Unit for Indonesia’s Fisheries Management Area (FMA) 713, 714 and 715. On the agenda, Measured Fishing Policy that, if steered wisely, could anchor the country’s push towards sustainable fisheries.

Born out of Government Regulation No. 11/2023, the scheme carves Indonesia’s seas into seven regulated zones, imposing quotas, licensing, and data-driven catch limits. Officials sell it as a necessary step to control overfishing, particularly by industrial fishers.

But controversy arose since the policy surfaced. Small-scale fishers fear the quotas will tip the scales in favor of larger vessels. Restrictions on fish aggregating devices (FADs) and the closure of spawning areas could slice deep into their earnings.

For MDPI, the forum was more than a bureaucratic exercise. As a member of the Indonesia Tuna Consortium, we made sure small-scale fishers belonged in the forum to voice their concerns. We made sure that every data we collected since 2013 with the small-scale fishers could reach the government’s tables.

MDPI believes that lasting ocean stewardship begins with strong policy that rests on reliable data. Much of the forum’s energy gravitated towards the Harvest Strategy: a suit of science-based fisheries management.

Implementing the strategy is not an easy mission. The strategy includes limiting FADs, closing spawning grounds, capping fishing days, and setting a Total Allowable Catch for each FMA. “The scientific nature of Harvest Strategy is not easy for small-scale fishers to grasp. It takes a lot of time and energy for fishers to study the strategy and comply,” said Yasmine Simbolon, MDPI Director.

Read also: Wailihang Tuna Fishing Tradition and the Struggles of Local Fishers

The government agrees. Acting Director General of Capture Fisheries, retired Police Commissioner General Lotharia Latif, stresses the urgency of accurate data collection for the policy’s success. “Nothing should go unrecorded. We need to know our fish stocks so management can be precise.”

Syahril Abd Raup, Director of Fisheries Resources Management, calls MDPI a “strategic partner” in connecting national policy with local needs. “From fisheries data improvement to community building, MDPI has been a valuable ally, bridging the government and the fishing community in policymaking,” he testified.

In high-level policy discussions, fisher voices are often drowned out by the hum of technical jargon. This time, MDPI made sure they carried through.

Syahidu, a tuna fisher from North Lombok (FMA 713), says he’s beginning to see the logic behind quota-based policy. “Thank you to MDPI for inviting us. Now we can understand the process too,” he said.

From Maluku (WPP 714), La Tohia calls for a fair FAD allocation and quota. “This forum has a lot to discuss… I hope FAD use will be limited and regulated in a truly fair way, and that quota distribution will not burden small-scale fishers,” he says. Meanwhile hi colleague, Ghafur from Ternate (FMA 715), takes a pragmatic view: “Managing fisheries isn’t as easy as flipping your hand. There are so many things to discuss and agree on.”

Their testimonies underline a simple truth: behind every regulation and data point are human lives, tethered to small boats in vast, restless waters.

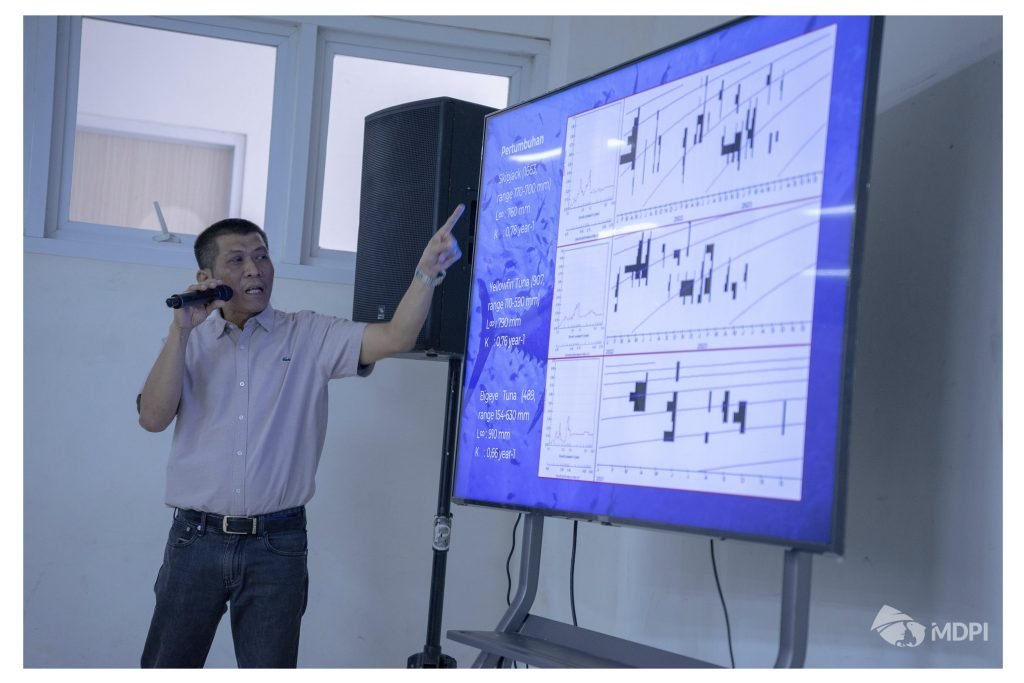

In breakout discussions for FMA 713, 714, 715, the conversation turned sharper. A glaring issue emerged: capture fisheries data is still patchy, especially for small-scale fishers and non-port landings.

Conserving fisheries require adequate data as its foundation. Hence Andi Irwan Nur, an academic from Halu Oleo University, calling the meeting a “historic milestone” for Indonesia’s capture fisheries. He emphasized that the forum’s output has become ‘the backbone of fisheries improvement in Indonesia’. “You can’t build fisheries improvement on assumptions,” he said.

MDPI’s Fisheries Lead, Putra Satria Timur, echoes the urgency: “Data is the foundation for making measured fishing work optimally.” This debate also highlighted a boulder that Indonesia still faces today: lack of adequate fisheries data owned by provincial governments.

Read also: Can Sustainable FAD Management Become Reality?

To plug the gaps, MDPI is training fishers to keep logbooks, digitizing the process to speed up data flow, and deepening collaboration with universities and researchers. The goal, according to MDPI’s Fisheries Lead, is to produce research that doesn’t just sit on shelves but shapes real-world fisheries management.

Another Opportunity Opens as the Forum Closes

On the final day, Makassar’s clouds broke open to blue. Delegates packed their bags—some clutching recommendation papers, others carrying follow-up notes. The Annual Meeting had ended, but its echoes lingered, stitching together hope and hard reality. Amid intense discussions, heated debates, and the government’s promises, a silver lining appeared: the stakeholders’ united commitment to protect the ocean.

For MDPI, this was just one knot in a much larger net—connecting data to policy, policy to people, and people to the long-term survival of the sea. Stakeholders’ support for quota-based fisheries policy and government’s commitment to fishers and fisheries improvement, are entangled in this network.

The road ahead is long, and sustainability won’t be secured by fishers or government alone. Public can take part in pushing for conservation and welfare-friendly policies. Our support is the extra wind needed to carry these commitments across Indonesia’s waters. If the voices heard in Makassar keep resonating, our ocean’s future might just have a fighting chance.

Buku ini disusun untuk mempermudah identifikasi spesies hewan ERS dan ETP yang

berinteraksi dengan nelayan selama aktivitas penangkapan tuna berlangsung. Semua

sumber ilustrasi gambar dan informasi pada buku ini telah dicantumkan pada daftar

referensi.

Kisah dari kampung nelayan kecil di 5 provinsi (NTB, Sulawesi Selatan, Sulawesi Utara, Maluku, Maluku Utara) diceritakan oleh masyarakat dampingan dan para pendamping MDPI. Mimpi besar untuk menjangkau lebih luas masyarakat pesisir dengan berupaya pada peningkatan kesejahteraan nelayan kecil melalui pengembangan kapasitas, membangun kemandirian, dan ketahanan ekonomi serta memperkuat institusi lokal demi mendukung perikanan berkelanjutan. Banyak pengalaman inspiratif, cerita sukses, kendala, kritikan, rasa bangga dan haru bercampur aduk dikisahkan dalam buku ini.

Penulis:

Gede Sughiarta, Nilam Ratna, Arroyan Suwarno, Alief Dharmawan,

Adjie Dharmasatya, Hairul Hadi, Muhammad Taeran, Muh. Alwi, Sahril,

Siti Zuleha, Sri Jalil, Hizran Sampalu, Karel Yerusa, Novita Ayu Wulandari,

M. Subhan Moerid.

Penyunting:

Gede Sughiarta, Arroyan Suwarno, Nilam Ratna, Alief Dharmawan

Desain/Layout:

Gede Sughiarta

Foto:

Yayasan MDPI, Gede Sughiarta

Illustrasi:

Panca Kumara